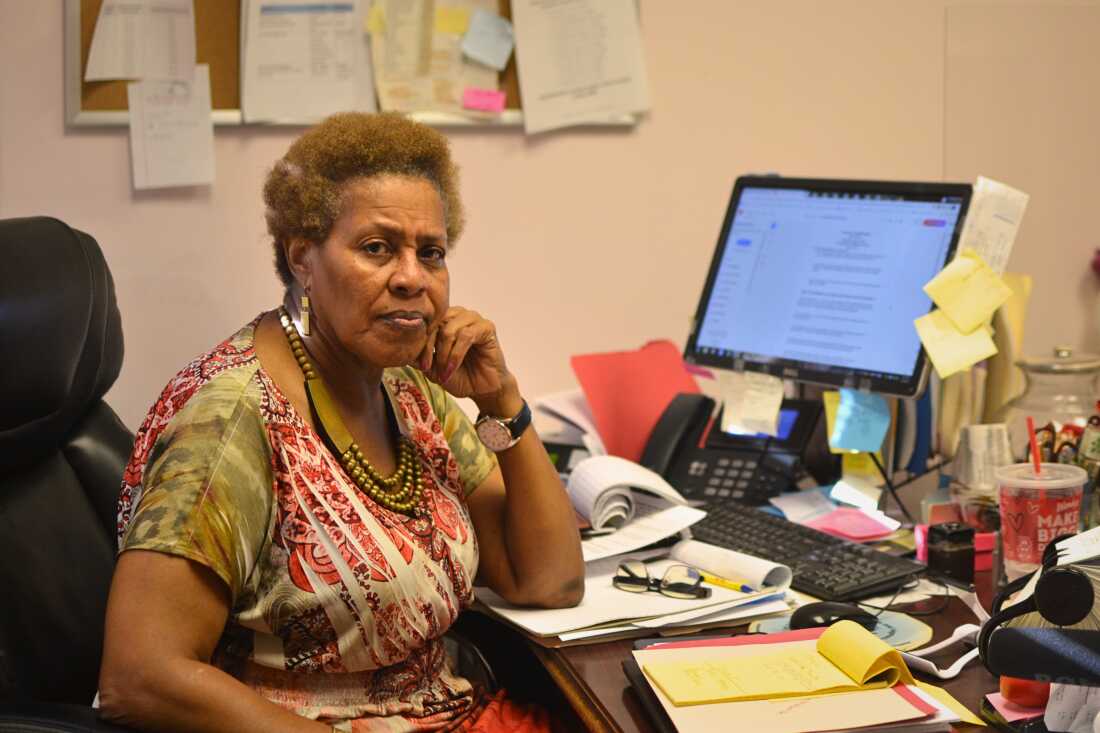

Rosie Brown, government director at East Carroll Group Motion Company in Lake Windfall, La., mentioned many individuals within the space battle to make ends meet. Medicaid growth was a lifeline for the city. Now, she mentioned, President Donald Trump’s tax and spending invoice might snatch it away.

Shalina Chatlani/Stateline

conceal caption

toggle caption

Shalina Chatlani/Stateline

LAKE PROVIDENCE, La. — East Carroll Parish sits within the northeastern nook of Louisiana, alongside the winding Mississippi River. Its seat, Lake Windfall, was as soon as a thriving agricultural hub of the area. Now, charred and dilapidated buildings dot the small metropolis middle. There are just a few gasoline stations, a handful of eating places — and little to no trade.

Mayor Bobby Amacker, 79, remembers a time when “you could not even stroll down the road” in Lake Windfall’s most important enterprise district as a result of “there have been so many individuals.”

“It is gone down tremendously within the final 50 years,” mentioned Amacker, a Democrat. “The city, it appears to be like prefer it’s drying up.”

Now, East Carroll residents stand to lose much more with the pending cutbacks to Medicaid, which covers many low-income individuals within the area.

Like many individuals in Louisiana, they obtained a lifeline when the state expanded Medicaid in 2016. Enlargement drove Louisiana’s uninsured charge to the bottom within the Deep South, at 8% in 2023 for working-age adults, in accordance with state knowledge, regardless of it having the highest poverty charge within the U.S. that 12 months.

State well being knowledge present the variety of individuals on Medicaid in East Carroll Parish elevated from about 53% in 2015 to about 64% in 2023, in accordance with state well being knowledge.

Many now fear these beneficial properties in protection might disappear. The tax and spending invoice President Donald Trump signed into legislation this summer time consists of practically $1 trillion in cuts over the subsequent decade to Medicaid, the joint state-federal medical insurance program for poor households and people.

Researchers from Princeton College estimate that 317,000 low-income Louisianans might lose well being protection due to the brand new legislation. Greater than 30,000 Mississippians too; that state has refused to increase Medicaid.

Lake Windfall Mayor Robert “Bobby” Amacker. With out Medicaid and Medicare, he says, many individuals in his city “would not have any type of well being care in any respect.”

Shalina Chatlani/KFF Well being Information

conceal caption

toggle caption

Shalina Chatlani/KFF Well being Information

The tax and spending legislation now imposes new work reporting necessities on Medicaid growth enrollees and can make them confirm eligibility each six months, as an alternative of yearly. This requirement, amongst others, will not kick in till 2027, after the midterm elections. It additionally limits a key financing technique — referred to as a supplier tax — that states depend on to present extra money to well being suppliers.

Nationwide, about 10 million individuals are anticipated to turn into uninsured over ten years due to the legislation, in accordance with the Congressional Finances Workplace. Throughout the deep South, Louisiana was the one state that expanded Medicaid.

“The way in which I’ve described this [law] proper now could be we all know there is a hurricane out within the Gulf,” mentioned Richard Roberson, president and CEO of the Mississippi Hospital Affiliation. “We do not know precisely what the class of the storm goes to be at landfall. However we all know we have to be ready for it.”

Struggling rural communities brace for affect

Within the Delta area, which incorporates communities in each Louisiana and Mississippi, the impacts are anticipated to be damaging.

Louisiana, the place nearly half of the state relied on Medicaid in 2023, might lose as much as $34 billion in federal Medicaid {dollars} within the subsequent decade, in accordance to KFF, a well being coverage analysis group. Mississippi might lose as much as $4 billion.

“The doctor group spoke out fairly closely towards this,” mentioned Dr. Brent Smith, a doctor at Delta Well being System in Greenville, Mississippi, about 50 miles northeast of Lake Windfall, throughout the river. “The truth that it nonetheless went although…was an actual sense of disconnect with what our legislators are doing and what we as a well being care group really feel like is the truth on the bottom.”

Residents of the Delta say they really feel equally distraught and are questioning how Congress could possibly be so blind to how a lot they’re struggling.

Dr. Brent Smith, left, a doctor at a major care clinic at Delta Well being System in Greenville, Miss. laughs with a co-worker.

Shalina Chatlani/Stateline

conceal caption

toggle caption

Shalina Chatlani/Stateline

“Why do you wanna knock somebody who does not have something and also you already received every little thing,” mentioned Sherila Ervin, who lives 20 minutes up the street from Lake Windfall in Oak Grove and has Medicaid protection. “It is gonna be actual tough when [the law] goes into impact.”

Ervin, 58, has been working at Oak Grove Excessive Faculty within the cafeteria, serving sizzling plates to kids for 25 years. She says it is one of many good, regular jobs obtainable on this space, however her earnings is barely round $1,500 per 30 days.

Her job affords well being advantages, however she will be able to’t afford the premiums on her wage. She depends on Medicaid for care, together with medicines for her hypertension. She mentioned the brand new work reporting necessities are fully unfair, and she or he’s fearful she is going to by accident lose her Medicaid.

“My coworkers are speaking about it on daily basis,” Ervin mentioned. “Lots of people in all probability will not even know till they go to the physician and so they haven’t any protection.”

In East Carroll Parish, discovering a job — not to mention a good-paying one with well being advantages — is tough, says Rosie Brown, government director on the East Carroll Group Motion Company, a nonprofit that helps low-income individuals with their utility payments. Most of the jobs obtainable on the town pay minimal wage, simply $7.25 an hour.

“We’ve got one financial institution. We’ve got one grocery store,” Brown mentioned. “Transportation is not simple both.”

Even a full-time job does not assure well being care protection. Nevada Qualls, 25, earns $12 an hour, working as a cashier at metropolis corridor in Lake Windfall. She qualifies for Medicaid growth protection, which is nice as a result of she will be able to’t afford the premiums for personal insurance coverage.

Due to the brand new Medicaid legislation, the mom-of-two must work additional laborious to maintain her protection. Qualls will face common work reporting necessities, extra frequent eligibility checks, in addition to the quarterly wage checks that Louisiana Medicaid already conducts.

“It’ll be aggravating,” Qualls mentioned. “It is one other factor so as to add to my load that’s already heavy.”

A large burden for states

States shall be required to implement work necessities by Jan. 1, 2027, giving them lower than a year-and-a-half to construct a reporting system and lift consciousness amongst enrollees. Relying on how Louisiana’s work reporting system capabilities, researchers estimate as much as 357,000 individuals might lose protection.

The legislation will now require adults who get Medicaid via growth to show they’re working or volunteering for 80 hours a month or going to high school part-time to maintain their protection, except they qualify for an exemption.

However, knowledge present most Medicaid enrollees are already working, KFF studies. When Arkansas carried out Medicaid work necessities in 2018 — the primary state to take action earlier than a courtroom struck it down — about 18,000 individuals had been disenrolled in lower than a 12 months, many for ‘paperwork’ causes, says Benjamin Sommers, a well being economist at Harvard T.H. Chan Faculty of Public Well being.

And there was no proof that work necessities had a constructive affect on employment, he mentioned.

“We’re leveling this bureaucratic purple tape on individuals, the overwhelming majority of whom are already doing the issues that we supposedly need them to do,” Sommers mentioned.

Courtney Foster, senior coverage adviser for Medicaid with the nonprofit Spend money on Louisiana, mentioned will probably be a “actually huge elevate” for states to manage the brand new Medicaid work reporting techniques.

“The hope is that [Louisiana] actually engages with individuals on the bottom, in addition to with community-based organizations that work with people who find themselves coated by Medicaid to create a system that really works,” Foster mentioned. “Let’s ensure that we are able to mitigate as a lot hurt as attainable.”

Mississippi can also be preparing, mentioned Roberson on the Mississippi Hospital Affiliation. With out Medicaid growth, the state’s enrollees will not be topic to work necessities, however the legislation’s financing modifications to the Medicaid program might strip lots of of thousands and thousands of {dollars} away from hospitals, mentioned Roberson.

‘Why are we going again?’

Jennifer Newton is the manager director of the Household Medical Clinic, a group well being middle in Lake Windfall, La.

Shalina Chatlani/Stateline

conceal caption

toggle caption

Shalina Chatlani/Stateline

The legislation did create a $50 billion rural well being fund, meant to offset spending cuts and assist preserve rural hospitals open. Roberson mentioned Mississippi is making use of and believes the state shall be awarded at the least $500 million over 5 years.

But when these funds do not make it to struggling hospitals, they may both shut or considerably reduce companies, he mentioned.

From her small, sunny workplace in East Carroll Parish, nurse Jennifer Newton, who oversees The Household Medical Clinic in Lake Windfall, does not perceive the assaults on Medicaid.

The group well being middle is among the few suppliers on the town, and half of its sufferers are on Medicaid.

Newton, who has labored in well being care within the space for many years, noticed first-hand how Medicaid growth made it attainable for extra sufferers to afford the care they desperately wanted.

“It is completely helped,” she mentioned. “Completely.”

In 2015, the 12 months earlier than Louisiana expanded Medicaid, the uninsured charge amongst working-age adults in East Carroll Parish was practically 35%. By 2021, that quantity was 12.7%.

“Why are we going again?” Newton requested. “We have made a lot progress.”

This story was produced as a part of a collaboration between Public Well being Watch and Stateline, which is a part of States Newsroom. It’s a part of “Uninsured in America,” a undertaking that focuses on life in America’s well being protection hole and the ten states that have not expanded Medicaid below the Reasonably priced Care Act.

Stateline reporter Shalina Chatlani will be reached at schatlani@stateline.org. Public Well being Watch reporter Kim Krisberg will be reached at kkrisberg@publichealthwatch.org.