Nomadic Jamaican-American author Claude McKay most likely by no means dreamed that 21st-century readers could be delving into his personal correspondence some 77 years after his loss of life. However that’s most likely a part of the skilled hazard (luck?) of being a literary luminary, or, as Yale College Press describes him, “one of many Harlem Renaissance’s brightest and most radical voices”.

The Press just lately launched Letters in Exile: Transnational Journeys of a Harlem Renaissance Author, edited by Brooks E. Hefner and Gary Edward Holcomb.

This can be a complete assortment of “never-before-published dispatches from the highway” with correspondents who’ve equally change into cultural icons: Langston Hughes, W. E. B. Du Bois, Marcus Garvey, Pauline Nardal, Arturo Alfonso Schomburg, Max Eastman and a gamut of different writers, editors, activists, and benefactors. The letters cowl the years 1916 to 1934 and have been written from varied cities, as McKay travelled extensively.

His daughter Ruth Hope McKay, whom the author apparently by no means met in life (maybe as a result of British authorities on the time prevented him from returning to Jamaica), offered and donated his papers to Yale College from 1964 on.

The papers embrace his letters to her as nicely, and solid a lightweight on this “singular determine of displacement, this critically productive internationalist, this Black Atlantic wanderer”, as a French translator has known as him. However studying one other’s correspondence, even that of a long-dead scribe, can really feel like an intrusion. It’s a sensation some readers might want to overcome.

Born in 1890 (or 1889) in Clarendon, Jamaica, McKay left the Caribbean island for america in 1912, and his wanderings would later take him to nations resembling Russia, England, France and Morocco, amongst others.

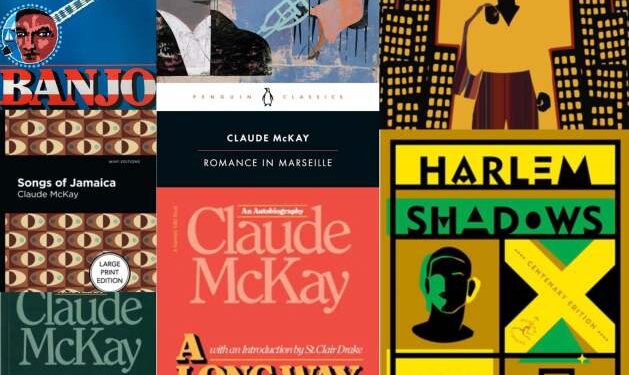

His acclaimed work consists of the poem “If We Should Die” (written in response to the racial violence in america in opposition to individuals of African descent in mid-1919), the poetry collections Songs of Jamaica and Harlem Shadows, and the novels House to Harlem, Banjo, and Banana Backside.

Years after his loss of life in 1948, students found manuscripts that will be posthumously printed: Amiable with Massive Enamel (written in 1941 and printed in 2017) and Romance in Marseille (written in 1933 and printed in 2020). McKay additionally authored a memoir titled A Lengthy Approach from House (1937).

Whereas he’s thought of a central determine within the Harlem Renaissance, McKay was a cosmopolitan mental – an writer forward of his time, writing about race, inequality, the legacy of slavery, queerness, and a variety of different subjects.

He wrote in a pointy, putting, usually ironic or satirical means, and Letters in Exile displays these identical qualities. The gathering “reveals McKay gossiping, cajoling, and confiding as he engages in spirited debates and challenges the political and creative questions of the day,” in line with the editors.

Among the most fascinating letters cope with France, the setting of a major a part of McKay’s oeuvre and a spot the place his literary stature has been rising over the previous decade, by a rush of recent translations, colloquia, and even a movie dedicated to his life: Claude McKay, From Harlem to Marseille (or in French, Claude McKay, de Harlem à Marseille), directed by Matthieu Verdeil and launched in 2021.

McKay was the “first twentieth-century Black writer related to america to be broadly celebrated in France,” write editors Hefner and Holcomb of their introduction. They are saying the letters present that France formed McKay’s world view, and that he thought of himself a Francophile in addition to a perpetual étranger.

By way of the chosen correspondence, we see McKay experiencing France in a wide range of methods – coping with winter insufficiently dressed, collaborating locally of multi-ethnic outsiders in Marseille, rubbing shoulders with varied personalities throughout the Années folles, or observing French colonialism in Morocco. And practically at all times in need of funds.

In Paris in January 1924, after a bout of illness, he wrote to New York-based social employee and activist Grace Campbell that he’d had the “bummest vacation” of his life: “I used to be down with the grippe for 10 days and solely compelled myself to rise up on New Yr’s day. I undergo as a result of I’m not correctly clothed to face the winter. I’m questioning if something will be performed over there to lift slightly cash to tide me over these dangerous occasions.”

A month later, he wrote to a different correspondent in regards to the “chilly wave” numbing his fingers and of getting to sleep together with his “outdated overcoat” subsequent to his pores and skin, whereas nonetheless not having the ability to maintain heat. He additionally discovered the “French buying and selling class” to be “horrible”, complaining that “they cheat me going and coming”.

Throughout his early time in France, he known as Marseilles a “nasty, repulsive metropolis”. However a couple of years later, writing to instructor and humanities patron Harold Jackman in 1927, McKay said: “I’m doing a e book on Marseille. It’s a troublesome, picturesque outdated metropolis and I might love to indicate it to you some day.”

Aside from references to his work, McKay mentioned international occasions in his correspondence, made his opinions recognized, and described relationships. His letters, say Hefner and Holcomb, are on the very least “an important companion to his most revolutionary writings, from the groundbreaking poetry he produced after he left Jamaica by his trailblazing novels and brief fiction and into his extraordinary memoirs and journalism.”

Whereas this might be true, and as insightful because the correspondence proves, many readers will nonetheless must reckon with the uncomfortable sensation of being a literary voyeur. – AM/SWAN

© Inter Press Service (20260113144017) — All Rights Reserved. Unique supply: Inter Press Service